The following is an article from the National Justice for Our Neighbors Newsletter:

After a two-year hiatus, San Antonio Region Justice for Our Neighbors joyously reopened its doors at Emanuel United Methodist Church on June 24, 2016.

For a ministry serving low-income immigrants, the key to success can be summed up in three words: location, location, and location. Emanuel UMC lies in the very heart of the West side of the city, home to many vulnerable immigrants living at or below the poverty level.

“People can use the bus or walk to get here,” explains Suzanne Isaacs, SARJFON’s Executive Director. “The board did not consider locating our clinic in any other part of San Antonio.”

In addition to its fortunate location, SARJFON is further blessed with a fully- engaged board, volunteers, an enthusiastic pastor, and vital support from the Rio Texas Conference of the United Methodist Church, church members, and the community.

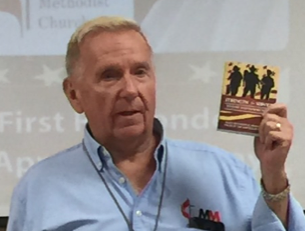

SARJFON also has a new attorney, Juan Castro, equally committed to the work and the immigrant neighbors he serves.

“She was there for me”

“I went to kindergarten not speaking a word of English,” recalls Juan, “but it wasn’t until first grade that the school realized I was just mimicking my classmates.” He grimaces slightly. “My teacher called on my parents and told them—through a translator—that I was going to have to repeat the year.”

Although Juan was born in New Orleans, he hadn’t heard much English from his Honduran parents, relatives or neighbors. There has been a large Honduran presence in New Orleans, headquarters for the banana empires of both the United and Standard Fruit Companies, since the last century. This immigrant population grew post-Katrina, when many Hondurans came to help with the rebuilding efforts, and the community is growing still.

On that day, as they sat in his family’s humble living room and listened as the translator relayed the teacher’s carefully-worded explanation, Juan realized that there was no way he was going to be left behind. Neither he nor his hard-working parents would accept failure. Fortunately, the school matched them up with a volunteer student teacher from the nearby University of New Orleans. She would not accept his failure, either. She took young Juan under her wing, tutoring him every day after school and on weekends, too.

“I had to hit the books hard,” Juan remembers. “All I did was study. My one goal was to pass first grade, so I wouldn’t be held back. And I did pass. I passed because of her.”

It’s a story Juan likes to tell volunteers he meets. Perhaps they think their volunteer efforts aren’t appreciated or important; that what they do doesn’t matter and doesn’t really change anything. But Juan knows this is wrong. A student teacher volunteered her time to teach a first-grader English, and the effects of that action have reverberated through all the years since, taking Juan to college, to law school, to his work as an attorney helping low-income and vulnerable immigrants. Who knows the lives touched, altered, changed, transformed because one young woman wouldn’t let a little boy fail first grade?

“I was even able to help my parents learn English.” Juan adds, grinning, “—in a very respectful way, of course.”

Back in Honduras, his parents had nothing. They came to the United States with nothing—nothing but hopes, dreams and the desire to succeed. Juan’s mother worked in an assembly line making ties, his father as a cleaner in hotels and movie theatres. Both eventually learned English well enough to attend community college. Both took the oath of US citizenship while their children watched.

And now? “My dad has a PhD and is a professor of finance where I got my undergraduate degree,” Juan says proudly, “and my mom is a kindergarten teacher.”

No one achieves the American dream alone. But everyone who achieves it passes it along to the next generation.

Paying it forward

In the summer of 2014, as thousands of unaccompanied migrant children streamed across the US-Mexico border, Juan volunteered at the makeshift housing shelter at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio. “The great thing about immigration law is that you can practice in any state,” says Juan, who worked alongside attorneys from every region of the country. There were so many attorneys who wanted to help.

The work was rewarding, but tough, says Juan. Day after day, listening to his teenaged clients’ harrowing stories, particularly those from young girls who had experienced sexual abuse, brutality, and intimidation—was often emotionally overwhelming.

For many of these kids, being sent back to the Northern Triangle countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras is tantamount to a death sentence. But for others,” Juan says, life isn’t necessarily better in the United States.

“I miss my family. It’s too hard here. I just want to go home,” they would tell him. For Juan, who knew these kids were abused and exposed to danger back in their home countries, and who wanted to continue making appeals for them, it was a devastating blow when his clients decided to give up.

“I wanted to fight for them, but not to mislead them,” he explains. “Just because you have touched ground here doesn’t mean all your problems will go away.”

“There is a saying in Spanish,” he adds softly. “La soledad es peor que la pobreza.”

Loneliness is worse than poverty.

Abiding by the JFON Model

The first clinic session is over and everyone is pleased with its success. Former SARJFON DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) clients are now volunteering at the clinic as translators. A Wesley nurse—provided by Methodist Healthcare Ministries—was on hand to provide basic health screening and help clients find health services in the area.

“We are tending to their legal status and their health at the same time—a Wesleyan emphasis that began with John Wesley,” Suzanne says with satisfaction.

Equally important, however, is the welcome, hospitality, and respect that each client receives when they walk through the doors of SARJFON or any of our 15 JFON sites and nearly 40 clinics throughout the nation.

“We had one lady who was hearing-impaired,” Juan relates. “She later confided in me that she was very grateful to have been treated so well by the hospitality crew. Unfortunately, she’d had a very negative experience at a previous organization that had virtually ignored her.”

At present, SARJFON will be focusing on helping immigrants obtain their Legal Permanent Status (green cards) and/or become naturalized citizens. It’s an area, Juan says, of great need in San Antonio.

“Immigrants don’t just want to stay in the shadows, work and send money back to their home countries,” says Juan. “They came to make a life here. They want to contribute, to participate, and to benefit their new home.”

“We,” Juan concludes, speaking now for his own family, his clients, and the generations of immigrants who have come before and will come after us, “are what makes America a great and unique nation.”